Go up to the Labs table of contents page

The purpose of this lab is to gain experience using hash tables by building an interesting application.

A hash table is a dictionary in which keys are mapped to array positions by a hash function. Having more than one key map to the same position is called a collision. There are many ways to resolve collisions, but they may be divided into two primary strategies: separate chaining and open addressing.

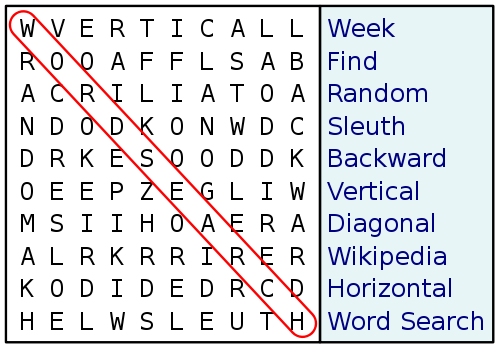

while loop: while (foo.good()).cout statements. Your output must conform to the output format described below!make creates MUST be called a.out. This means that you must NOT specify a -o flag to clang++, otherwise it will not work on the grading server! Just let clang++ name it the default without specifying a -o flag.Consider the problem called word search, illustrated in the diagram below.

In this 10x10 grid of letters, the goal is to find words in the puzzle in any of the eight directions. The word circled in red is in the south-east direction. Words can go backward (although none do in this example), but they cannot "wrap around" from one side to the other (or from top to bottom, etc.).

For the purposes of this lab, your program will be presented with a grid of letters and a dictionary of words. All words in the dictionary that are in the grid, in any of the 8 directions, are to be outputted.

A string of letters from the grid will depend on four values:

This implies that your code will have quad-nested for loops.

The goal for the pre-lab is to get your puzzle solver working, using a hash table that you write, without worrying about efficiency. The goal of the post-lab is to increase it's efficiency.

A few notes about the length of the words: the program to implement will not consider words of length less than 3, and the maximum word length is a constant (which is defined as the longest word in the input dictionary file provided to the program at run-time).

There are a number of optimizations that one can implement, a few of which are mentioned here. Depending on how you implement them, they may not work all that well, of course.

For this lab you need to implement a solution to the word puzzle problem described above.

The basic idea is that given a dictionary of words, we want to write a program that finds all instances of those words in a grid of letters. This is similar to the word search puzzles where you circle the words, horizontally, vertically or diagonally in the grid. As specified above, words can appear in any order (including backwards) in the puzzle. However, in our case you are not given the list of words to find, you are merely given the grid and told to find all the English words in the grid. You will be given a dictionary (list) of English words, but you should expect this to be very large. You will want to put this list of words into a hash table to facilitate quickly checking if a particular combination of letters is a word in the dictionary.

You must write your own hash table for this lab. You will be expected to be able to implement a hash table after completing the lab. You should definitely stay away from templates for your implementation. You may use separate chaining with buckets of any type you wish (linked list, etc., but not vectors) or open addressing with any collision resolution strategy you wish (linear probing, quadratic probing, double hashing). The hash table itself will need to be an array or vector (you may use the STL vector for this); your separate chaining secondary data structure may also be from the STL. Thus, you may use any data structures that you want EXCEPT a vector of vectors, which is specifically forbidden. You can use a vector of linked lists, however. Obviously, you cannot use any STL hash table implementation.

We are not as interested in how fast this runs for the pre-lab; the fast implementation is for the post-lab.

Your program MUST take in the file names as command-line parameters, not as inputs to the program. The first is the dictionary file, the second is the grid file. Indeed, the program will ask for NO input, as the two inputs necessary (the two file names) are passed in as command-line parameters. See the slide set on arrays if you need a refresher on command-line parameters; you can also see the cmdlineparams.cpp (src) file.

The task for the pre-lab is to get the code working. Optimization (reducing memory use, choosing the right collision resolution method, the right secondary data structure, different hash functions, etc.) is left to the post-lab. You should have a fully function program when you come to lab on Tuesday.

As discussed in lecture, a hash table needs to be a prime number in size in order to work. You can adapt the code in the primenumber.cpp (src) file to determine the next highest prime number (of course, the next highest prime number is determined after you double the size of your original hash table).

Creating a dynamic 2-D array in C++ is more difficult than it should be -- one solution is to create a vector of vectors, but that is not the most efficient means to do it. For this lab, you can just create a 500x500 static array, and can assume that you will not have your program run on larger input grids. This is not very elegant, but it will work until we go over dynamic array creation in lecture.

We provide you with a second C++ file, getWordInGrid.cpp (src), that provides two useful functions. The first is readInGrid(), which will read in a grid file using C++ streams. The grid file format (specified below) is very specific, and this code follows that specification. Note that the open() method to ifstream (and ofstream) takes in a C-style string, NOT a C++-style string (you can convert use the string::c_str() method to convert a C++ string to a C string). The second function, getWordInGrid(), will return a word in a 2-D grid of letters in a given direction. Extensive comments in the getWordInGrid.cpp file explain how to use these functions. Note that a couple of the items in that file require different #include headers, as mentioned in the comments.

You must understand the concepts in the getWordInGrid.cpp file! In particular, you will be expected to be able to program C++ streams for file input in future labs and exams. And you will need to write your own C++ stream input routines to read in the dictionary file. If there is anything there that you are confused about, see the Reading links at the beginning of this lab document.

Somehow your program will need to handle input dictionaries of various sizes, and creating the appropriate size hash table. To get the program working the first time, you can just hard code a prime number table size. But at some point, you will have to handle different size hash tables.

rehash() function that will double the size of the array, hash all the old values into the new table, and then remove the old table.Note that you do not have to implement delete() functionality for your hash table.

In an effort to make this program work with the grading system, you should submit the following files:

You can submit other files, if you want, up to the maximum allowed by the submission system. We are going to compile your code with make. Your program must compile! And it must compile with just the make command! Don't specify a -o option with clang++, so that it will default to a.out. Your program should also conform to the input and output requirements listed in the pre-lab procedure, discussed below, as that is how it will be tested. If it doesn't conform to these guidelines, you will receive points off!

Input grids: You can expect an input grid file in which the first line is the number of rows, and the second is the number of columns, both as ASCII text digits in unsigned decimal integers. The third line is the grid data, with no spaces (i.e. it will be rows X cols number of characters). Several example grids available in the labs/lab06/data/ directory. Grids will not include whitespace, numbers, punctuation, or special characters.

Dictionary files: The dictionary can be assumed to contain one word per line. The longest word in our data files is 22 letters. Words which contain a space or other special character (& or ' or -) or number may occur in the dictionary, but would never appear in a valid grid. Your program should be able to handle dictionaries with such words, although you are not required to put them into the hash table.

Timing: Timer routines are available in the provided source code (timer.cpp (src), timer.h (src), and timer_test.cpp (src)). We are interested in timing how long it takes to find all valid words in a grid. We are NOT interested in how long it takes to fill up the hash table initially. Therefore you need to place your timing calls around the outermost loop that contains code in which the grid is actually searched.

Valid words: Your program should only report words with three or more letters -- there are simply too many hits if one and two letter words are allowed, and it's difficult to judge correctness, even on very small word searches. This size (i.e. 3) can be hard-coded into your program. Depending on how you've implemented your loop, this could be something as simple as a single test and a continue statement. One and two letter words may occur in the dictionary file, but you are not required to put them in your hash table (although it is fine to do so).

Upper case / lower case: You should be prepared for any English language alphabet characters of both cases. Searches are case-sensitive. Thus, if the word in the dictionary is 'Foo', it should not register a match to the text 'foo' in the grid.

Duplicates: If a word occurs more than once in a grid, then each instance should be treated as a separate word.

In an effort to make it easier to determine if the program is working properly or not, we want to standardize the output format. Below is the 4x7.out.txt file:

N (3, 2): text

E (0, 3): sod

N (2, 5): fad

E (1, 0): pax

NW(3, 6): eft

E (2, 0): ace

W (2, 4): tee

NE(2, 4): tat

SW(0, 6): tat

9 words found

Found all words in 0.000835 secondsWe aren't so worried about the exact spacing, as we can easily (and automatically) ignore that when comparing your output to the desired output. But the characters and punctuation should all be the same. Note that the order the words are found does not matter, although they should all be listed before the last 2 summary lines at the bottom. The in-lab discusses how to directly compare your output to the expected output (while ignoring spaces and word order) - see the "Input and Output" section of the in-lab.

We are going to execute your code as follows:

./a.out <dictionary_file> <grid_file>If your program attempts to get the dictionary file and grid file through standard input, it will not work properly and you will lose all credit. So be sure to use command-line parameters! See the section on handling command-line parameters, above.

So far, we have learned a number of clang++ flags (-o, -g, -Wall, -c, -MM). If you forget what these do, look at the compilation flags page. We'll learn one other flag today: -O2.

There are many times when we want our executable program to run as fast as possible. An example of this is the current lab -- as we are testing our programs for speed (and we want them to run fast), we want to tell the compiler to write an optimized executable. To do this, we specify the -O2 flag (notice that the 'O' is capitalized). The 'O' part stands for optimization level. There are multiple optimization levels that clang++ provides, each with benefits and drawbacks. The only allowable optimization level for this lab is 2 (i.e. '-O2', not any other number after the 'O'). For example, to compile this program, we would enter:

clang++ -O2 -Wall wordPuzzle.cpp timer.cpp hashTable.cppIf the only files with a .cpp extension in the current directory are those three files, then we could also enter:

clang++ -O2 -Wall *.cppIf we wanted to use the -c flag (such as through a Makefile), then the commands would be:

clang++ -O2 -c wordPuzzle.cpp

clang++ -O2 -c timer.cpp

clang++ -O2 -c hashTable.cpp

clang++ -O2 wordPuzzle.o timer.o hashTable.oNote that on this last one, that the -O2 flag must be used on each of the individual compilations as well as the final link. Thus, when put into a Makefile, you can make the CXX macro be clang++ -O2, so it will apply to all of the compilations.

We could always tell the compiler to create an optimized executable file by always using the -O2 flag. But there are some disadvantages to doing so. Debugging the program in gdb is much harder (if not impossible) with an optimized executable -- much of the debugging information is stripped out of the executable to improve the speed. Thus, if you want to debug your program, you will have to remove the -O2 flag (and put in the -g flag, of course). Also, the compiler takes longer to compile the program when optimizing. For these reasons (and others), programmers usually don't use the -O2 flag until they know the program works, and thus want the additional speed improvement.

Try compiling your program both with and without the -O2 flag. Run the program both times. Do you notice a difference in the timed speed of the program? Our test program decreased in execution time from about 15 seconds to 12 seconds with the -O2 flag.

When we are running the programs, we will need to make sure that they are reporting the same results. To do so, we will need to save the output into a file, and then make sure that file matches the sample input file.

To redirect output to a file, we enter the following command (we've seen pipes before -- in section 3 of the first Unix tutorial -- so this should be familiar material).

./a.out words2.txt 300x300.grid.txt > output.txtRecall that this command will OVERWRITE output.txt (if it exists), and save all the output from the executable into that file. This program does not ask for input; if it did, we would not see the prompt, but would still have to provide the input.

Once the program is completed, we will need to see if that file is the same as the sample input. To do so, enter the following command. We'll assume, for this example, that we are using the 300x300 grid, and words2.txt.

diff output.txt 300x300.words2.out.txtThis will examine the two files byte-by-byte, and look for differences. If there are no differences, then diff will not print out ANY output. If there are differences, then they will be printed to the screen. This means that if diff prints anything, then your program is NOT producing the same results as we are expecting. All hope is not lost, though! If you look at the two files (you can load them up both in Emacs), it may very well be that the difference is in formatting -- you use two spaces, we use one space, for example.

Keep in mind that your program execution may include a bit of additional output -- such as the prompts for the filenames, the timing information, etc. If that is the only difference between output.txt and the sample output, then that's fine.

If the files are not sorted the same -- meaning that the words listed are the same, but in a different order -- then diff will report differences between the files. You can use the Unix 'sort' command to sort BOTH files before comparison to fix this:

./a.out words2.txt 300x300.grid.txt | sort > output.txt

sort 300x300.words2.out.txt > words2.sorted.out.txt

diff output.txt words2.sorted.out.txtIf there are a lot of differences, then you should run your program on a small grid with the smaller word file (i.e. words2.txt). Once you solve the differences with the smaller grid file and word file, most of the differences with the larger grid/word files should disappear.

Lastly, you can provide the -w flag to diff to have it ignore all whitespace on the lines it is comparing.

Through the various programming languages we've seen (Java, C++, etc.), we can make a computer do many things. Yet there are still limitations to what we can do in these languages. How could you get a directory listing in Java, for example? Or easily invoke Unix commands from C++? While these are certainly possible, they are often difficult to accomplish.

Yet programmers often have a need to do these sorts of things. For example, a script that we wrote takes all the submissions made to the submission server, compiles and executes them, and saves the execution output to various files. This allows the compilation and execution to be automated, and thus saves the graders a lot of time.

The shell is the command-line interface that you use when you are interactively using Unix (i.e. the Linux command line). There are many shells out there, some of the more popular being bash, csh, and ksh. Bash is the standard shell, that the vast majority of system scripts are written in (such as for Linux). Csh (and tcsh, its successor) is a shell with C-like syntax. Ksh is a more advanced shell that has greater capabilities, but has a steep learning curve. We'll be using bash for this tutorial, as it is the default on most systems, including Linux.

The original Unix shell was written by Stephen Bourne and released 1978. It was just called 'sh', which is short for 'shell'. In 1987, Brian Fox updated the shell, and decided to name it 'Bourne-again shell', a play on the original author's name. Hence the name of 'bash'.

A shell script, then, is a series of commands for the shell to execute. Shell scripts started off, many years ago, as just a way to have a series of simple commands in one place. Indeed, this is largely what batch files are in Windows and DOS (remember autoexec.bat?). Over time, additional functionality was added to these scripts, mostly the things we are used to in programming languages, such as variables and control structures (for and while loops, if and case conditionals, etc.). Today, shell scripts are a very powerful programming language that one can use to do many things.

Shell scripts are useful when one needs to call a large number of Unix commands (such as the aforementioned compilation/execution example). Significant computation, such as finding words in a word puzzle, or a lot of arithmetic, are not well suited to shell scripts.

In this lab, we will be learning about shell scripts. Read the shell script tutorial for this lab, which is the first 6 sections (through and including 'exit status') of the Wikibooks article on Bash Shell Scripting. Much of the earlier material in this article should be familmiar to you from the Unix tutorials that you did for labs 3 and 4. The remaining sections of that article will be the tutorial for the next lab, so feel free to read on, if you are interested.

Once you have read the tutorial, you will need to write a shell script that will prompt the user for the dictionary and grid file names used by your word puzzle executable. It will the run the program five times using those parameters. Note that it is running the same program five times with the same parameters. It will record the time of each execution run, and, once the runs are completed, print out the average run time. Note that you have not yet seen conditions (if or case) or loops (for or while) in shell scripts, so we do not expect your script to have either of these -- you should just have 5 separate commands without a loop.

To make your life easier, you can modify your word puzzle program to print out the total time taken as the last line of output. THIS MUST BE AN INTEGER VALUE! Otherwise else the shell script will have problems (floating point arithmetic in bash is viable, but more complicated, so we'll stick with integer arithmetic). Thus, you should multiply the timing result by 1000, and then print it out (hence you are printing out the number of milliseconds that the program took). You should use the timer's getTime() method for this. You can then capture that line by piping it through the tail -1 command -- a brief introduction on how to do all of this is presented here. The back quote (on the same key as the tilde (~), which is usually to the left of the digit 1) tells a shell script to run the program, and use the output for something else (as opposed to displaying the output to the screen). For example, the following line would run the program (called a.out), only keep the last line, and save that output to a variable.

RUNNING_TIME=`./a.out | tail -1`Important note: your shell script MUST call a.out, and not anything else. We are going to test it on a Linux box, and if it calls anything else, it won't work, and you won't get credit.

Armed with this, the rest of the required concepts for the shell script are in first six sections of the article. This script should be named averagetime.sh.

As you are going through the tutorial, if there is a Unix command that you do not know (or you once knew and have since forgotten), you can find out more information about that command by entering man command at the Unix prompt. This brings up the manual for that command, including all of the command-line parameters.

A few thoughts to help you with your shell script. If you are unsure if something is working, you can always print out the value of the variable through the echo command. And you need not worry about the decimal precision of the average -- the result of using arithmetic expansion $(( ... )) with the sum over the number of runs is fine -- recall that the script has been modified to only print out an integer value (using arithmetic expansion $(( ... )) with floating point values will have issues).

Your script should have comments (anything on a line after a '#' is a comment). Our solution was 10-15 lines, not counting comments.

Below are a few notes to keep in mind when writing your shell script. Bash is a very powerful language, but it can be rather finicky and unforgiving with syntax.

averagetime.sh, and should have #!/bin/bash as the very first line of the script#!/bin/bash, it will use the wrong shell, and your program won't work properly!./averagetime.sh. If you get a complaint about that ('permission denied', for example), enter this command: chmod 755 averagetime.sh. This tells your Unix system that averagetime.sh is a program that can be executed (remember chmod?).One of the deliverables for the in-lab is a PDF document named inlab6.pdf. It must be in PDF format! See How to convert a file to PDF for details about creating a PDF file.

This report should contain items such as:

Basically, we want a summary of your thoughts and experiences with the lab at this point, as well as the results from your timed runs. As this is an in-lab report, we don't expect it to be very long winded -- just enough to answer those questions is sufficient.

You will need to optimize your code for the solution to the word puzzle, as well as the post-lab report described below.

Your coding task for the post-lab is to optimize your program. At this point, your timing code should be in place, and your in-lab shell script should be able to automate the running and timing of your program.

First, record how long it takes to run your un-optimized program. We will need this value later. All these values should be recorded when the executable being run was compiled with the -O2 flag.

You will need to implement optimizations to your program. In addition to the optimizations described above (in the section that describes the word puzzle problem), some other possible optimizations include:

Keep track of what you tried -- if you try each of the collision resolution strategies, and find that the original one you used is faster, record all of this in the post-lab report, along with the times from the other strategies.

There are a couple of restrictions as to what optimizations you may use. You may not write assembly code for your solution; it must be valid C++ code. You may not use an optimization level beyond -O2. You may use other clang++ flags, if that helps, but you can't use -O3, -O4, etc. The reason for this last one is that a program is not guaranteed to function the same when using optimizations beyond -O2. Note that although we are trying to get you to think at least a little bit about making your program fast, keep in mind that we still want clean, correct, readable code. Your solutions will be judged on style and correctness.

How much time and effort should you put into the optimizations? We want to see (by looking at your code and the post-lab report) that you have spent thought, time, and effort on the optimizations. If you can get your code to run in under 2-3 seconds (this has been done), then there probably aren't many more optimizations that you can perform. However, if your pre-lab code already runs that fast, you still need to add some additional optimizations. But this gives you a rough idea of what to shoot for in terms of execution time.

When reporting times for the post-lab report, all times must be with the words2.txt and 300x300.grid.txt files as the input. All programs must be compiled with -O2. You can do this on any computer, but make sure all your times are done on the same computer for comparison consistency. The timing code must be as specified in the pre-lab section (i.e. around the hash table usage, not the hash table creation).

Feel free to experiment with different hash functions and different implementations of hash tables. Part of the assignment is to combine what you have learned about picking a good hash function and appropriate table size with big-theta evaluations of running times of your algorithm.

One of the deliverables for the post-lab is a PDF document named postlab6.pdf. It must be in PDF format! See How to convert a file to PDF for details about creating a PDF file.

If you single-space your report, you can divide the page lengths listed below by a factor of 2. If you single space your report and include a lot of blank space with tables, that's not what we are looking for here.

Include the big-theta running time of your application, and a full explanation as to why. This should be half a page or so. This should address only the word-search portion of your application -- not the reading of input files, hash table creation, etc. This big-Theta runtime should take into account any and all optimizations that you made. Please do this in terms of r (rows), c (columns), and w (words). You can assume that the maximum word size is some small constant.

Include the timing information for your application (as described at the end of the in-lab section). This should also be half a page or more. You can do this on any machine and data files, just use the same machine and files for all tests. Be sure to specify which files and machine you used. Show timing results (use the timer placement as we used in lab) for:

Describe the optimizations you used, and the times that resulted. You should also include the overall speedup of your optimizations. If your original running time (unoptimized) was x, and your final running time was y, then the speedup is just x/y. For example, if your program took 10 second to run unoptimized, and 5 seconds after optimizations, you have a speedup of 2.0. You should have a lot to talk about in this section -- the optimizations you tried, why they worked (or didn't work), problems you encountered, numbered results, etc -- two pages or so is what we are looking for here.